Finding Truth in Fantasy

As a child, my reality was quite small. My world was the little yellow house on Tennyson Street. Daily life consisted of playing with my sister in the backyard and making potions for our cat, who didn’t always appreciate the offerings. But beyond our day-to-day truths, my sister and I acknowledged an alternate reality.

As a child, my reality was quite small. My world was the little yellow house on Tennyson Street. Daily life consisted of playing with my sister in the backyard and making potions for our cat, who didn’t always appreciate the offerings. But beyond our day-to-day truths, my sister and I acknowledged an alternate reality.

Our backyard ended in an upward slope covered with ivy that we called “Turtle Hill.” This was because maybe we saw a turtle in the vines once, or maybe it was because the girl we sometimes thought we saw up there at-the-edge-of-our-reality, had tens of turtles that would sometimes escape. We never actually met that girl, if there was a girl, and yet I still have a clear mental picture of an ivy-covered incline teeming with turtles and the mysterious wavy-haired proprietor at its peak. The truth of this matter will never be known.

Adults most often see clear delineations between what is real and what is imagined. For children, those lines are capable of bending and blurring in wonderful ways. It is this fleeting superpower that enables young learners to fill the gaps in their experience and knowledge with imagined truths. These truths can offer possibilities in times of peace, and comfort in times of chaos.

Stories are vital to truth-seekers because they have the power to expand small realities. Seeing other worlds allows readers to imagine new scenarios from which to build upon or through which to adapt. Because fantasy is most highly developed in children, fantastic stories have the potential to make even more impact. Fairy tales free themselves from conventional lines of thought and invite readers to see common problems with fresh eyes and questioning minds. When a story travels to impossible realms, its premise is often recognizable but not weighed down in earthly specifics, allowing its passengers to see concepts more abstractly. Imagination itself is the capacity to evolve and take (often messy) mental leaps to places that don’t yet exist. Imagination is essential to human progress. This blurring of perception and reality propels us forward, and it is often the important difference between adapting to what is and shaping what will be.

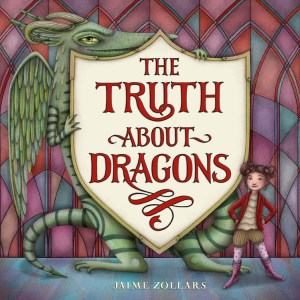

As an illustrator and creator of stories for children, I find great interest in weaving fantasy and reality for readers in ways that are meaningful, memorable, and just a little bit messy. The Truth About Dragons is a picture book about perception, and how the world looks different when we’re afraid. It follows Annabelle on her first day of school, where she encounters some terribly wild dragons. Instead of running away, she bravely looks past her fears to uncover the truth. When Annabelle allows herself to make connections one by one, the dragons slowly appear as human classmates who come to find that ruling their castles is better with friends.

I hope readers with anxiety find practical meaning in this book about how problems often appear bigger than they are, and I would like to think that its detailed imagery of dragons changing into children will make it memorable. But because the book is about the messiness of confronting chaos, I left fillable gaps for imagined truths and moments of gray that crack windows to discovery. The text does not explain the visual changes that transpire; The Truth About Dragons is only revealed to those willing to figure it out. And not everyone will figure it out, at least not right away. I know this because I read the book to a class of first graders. While they had some very interesting theories, it took a few tries before a kid in the back tentatively raised his hand and simply declared that these friends were never really dragons at all. His statement was initially met with disbelief from the seven-year-old set. But realization followed in waves, as they pieced it together and excitedly went through the book again, pointing out the clues they had, in fact, missed. A wonderful discussion was had, and I believe that its lessons will stick. The most meaningful (and stickiest) truths are not ordained, but are imagined and discovered on one’s own.

Fantastic tales find children in their shared bedrooms in small yellow houses and invite them to wild rumpuses and epic dog parties. Fantastic tales feel possible to kids who understand that knowledge is limited, but imagination is very very big. And, of course, fantastic tales offer hope when your childhood cat runs off again, because you know with all of your heart that he is probably-maybe-definitely-you-think just visiting the wavy-haired girl and her turtles for a short while, and that he is okay, because when the light hits just right at the top of the hill, you think you can see his silhouette. As a child, I sought comfort in imagined fairy tales, and as an adult, I believe, as G.K. Chesterton famously wrote, that “fairy tales are more than true… .” They ring true in our bones, summoning our feelings and validating our emotions, “…not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.”