6 Must-Read New Noir Novels

Dark alleys, moral gray zones, and characters who rarely get what they deserve—noir has always thrived on the tension between truth and illusion. Whether set in rain-slicked city streets or quiet towns hiding dangerous secrets, the best noir novels pull readers into worlds where every choice has a cost and every revelation comes a little too late.

Here are six noir novels we’re reading right now that deserve a spot on your nightstand.

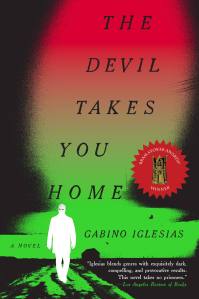

Buried in debt due to his young daughter’s illness, his marriage at the brink, Mario reluctantly takes a job as a hitman, surprising himself with his proclivity for violence. After tragedy destroys the life he knew, Mario agrees to one final job: hijack a cartel’s cash shipment before it reaches Mexico. Along with an old friend and a cartel-insider named Juanca, Mario sets off on the near-suicidal mission, which will leave him with either a cool $200,000 or a bullet in the skull. But the path to reward or ruin is never as straight as it seems. As the three complicated men travel through the endless landscape of Texas, across the border and back, their hidden motivations are laid bare alongside nightmarish encounters that defy explanation. One thing is certain: even if Mario makes it out alive, he won’t return the same.

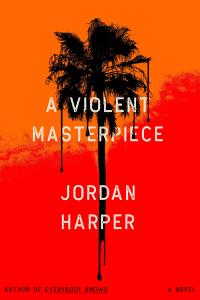

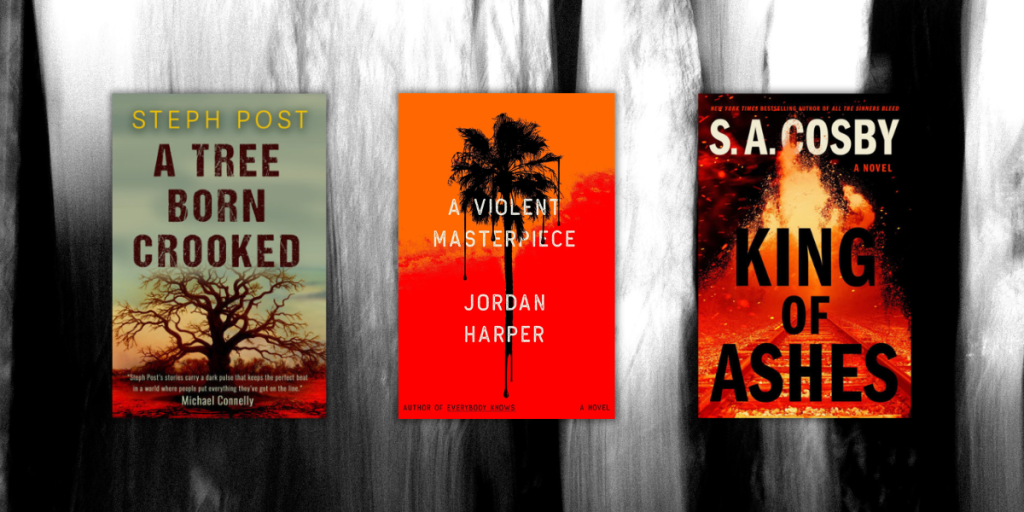

As chaos spreads, three unlikely figures—a livestreaming nightcrawler, a streetwise defense lawyer, and a concierge for the ultra-rich—begin investigating from different angles. Their searches collide, exposing a dark network of wealth, power, and violence at the heart of the city.

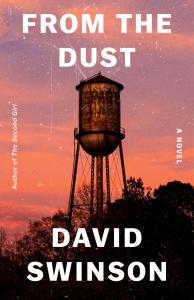

The chief of the town’s small police jurisdiction, who is also a family friend, asks for Graham’s assistance. Graham’s instincts immediately kick in and he soon discovers there’s more to the area—the people, its brutally quiet, sophisticated hierarchies—than he or his family ever knew.

David Swinson’s latest novel is a soulful, rural noir story about belief: the extremities to which it pushes a community, the fear it instills in the hearts of adherents and doubters alike, and need for it nevertheless. As Graham delves deeper into the strange and then stranger circumstances of the murders, his own beliefs become challenged. What do you finally stand for when you’ve got nothing left to lose?

When Roman Carruthers returns home after his father’s suspicious car crash, he finds his family in crisis: his brother Dante owes dangerous criminals, and his sister Neveah is struggling to keep their father’s crematorium running in their fading Virginia town.

Roman has the money—and the financial savvy—to try to fix things, but he quickly realizes he’s dealing with real gangsters. As the danger closes in, he offers the only thing he has left to save his brother: himself and his skills. Meanwhile, Neveah searches for the truth about their mother’s long-ago disappearance, uncovering secrets that threaten to tear the family apart.

Located in Florida, Crystal Springs is a place where dreams are born to die. Once back in the rural and stagnant town, James learns that his brother’s crimes have caught up to him. Despite his hesitations, James teams up with a local bartender and hatches a plan to save his brother’s life.

Soon, James finds himself on a whirlwind road trip across the desolate Florida panhandle, trying to outrun an enemy more dangerous than he knows. With bullets in the air and the ghosts of his past haunting him at every turn, James is forced to decide just how much he’s willing to risk to save his family.